This eFLYER was developed in HTML for viewing with Microsoft Internet Explorer while connected to the Internet: View Online.

To ensure delivery to your inbox, please add eFLYER@barnstormers.com to your address book or list of approved senders. |

|

ISSUE

110 - March 2010

Over 8,000 Total Ads Listed

1,000+ NEW Ads Per Week

|

| Heroes |

By David Rose

San Diego, California |

They ran the Iditarod this week. You

know, bundle up, hook up the dogs and race 1049+ miles across

Alaska.

Lance Mackey won it, again, for his fourth straight

time. Hans Gatt managed second and Jeff King third.

So when

I saw the news story covering it, my question was why? Sure,

it’s great to get out there and race your car, airplane,

horse, or even your dogsled. But my question was why 1049+

miles over 8 or 9 days in the dead of the freezing winter?

And why does it run from Anchorage (Willows actually) to Nome? |

|

Finding

out why drew me in to one of those special stories, common

knowledge to some, but totally unknown to the rest of us. Finding

out why drew me in to one of those special stories, common

knowledge to some, but totally unknown to the rest of us.

First

you have to appreciate what winter meant in Nome Alaska in

1924 (picture left, Nome in Winter). It literally

closed the town to the outside world. The harbor froze out

shipping, snow and ice covered the roads, completely closing

them and the airplanes of 1924 never challenged the constant

blizzard conditions. In winter the town and the surrounding

Inuit villages were as isolated from the rest of the world

as the moon.

Which

was fine, most of the time. In normal circumstances the residents

coped well. They kept in contact with one another; checked on

the neighbors; stayed aware of who came and went (picture

right, Front Street in Nome, Alaska). Which

was fine, most of the time. In normal circumstances the residents

coped well. They kept in contact with one another; checked on

the neighbors; stayed aware of who came and went (picture

right, Front Street in Nome, Alaska).

But in that

winter of 1924, something else had joined them. Just a cold most

thought, or influenza at worst. Sore throats, a little cough,

a little fever, some dizziness; the common cold was spreading

through town. Or so it seemed to Dr. Curtis Welch. But by early

January Dr. Welch, who essentially represented all of Nomes medical

care, began to think his diagnosis of the common cold might bear

a second thought. Weeks had passed and the little epidemic wasn't

abating as it should have. |

Dr. Welch came to realize that this had

to be Diphtheria. Highly contagious, symptoms identical to

the common cold. Bad cases of Diphtheria lead to liver and

heart failure and the patient dies.

Still, not a problem, once

it’s properly diagnosed medications deal with it quit

well. Diphtheria antitoxins cure it and there were thousands

of units available; until they discovered the antitoxins were

out of date; expired the year before and now potentially lethal.

In desperation Dr. Welch telegraphed the US Health Service

and they were able to track down 30,000 units of the Diphtheria

antitoxin in Anchorage. But Anchorage! It lay 600 miles as

the crow flys across the most forbidding winter landscape on

the planet. |

Dogsleds

would be the only way. But impossible. Not in the dead of winter.

Not over these mountainous, freezing, utterly barren landscapes.

Plus the the antitoxin was packaged in fragile glass phials

and if they didn’t break the serum could freeze on the

way. They had to try. Wrapping the phials in fur against the

cold, they padded them as best they could. From the rail station

in Anchorage they traveled by train 200 miles north to Nenana.

But from Nenana, the little 20 pound package of antitoxin was

still 675 miles across sub-zero wasteland from Nome.

Impossible.

A desperate attempt to deliver the antitoxin and save the villages

had to be made by dogsled. Here the telegraph proved to be

their godsend as with it they were able to line up relief teams

all along the way to relay the serum.

So why do I bring this

up here on an aircraft site? Because if you’ve followed

many of my stories in past Eflyers you know I like to write

about heroes and it took a lot of heroism to save the people

living around Nome that winter. So why do I bring this

up here on an aircraft site? Because if you’ve followed

many of my stories in past Eflyers you know I like to write

about heroes and it took a lot of heroism to save the people

living around Nome that winter.

The attempt to save them involved

no fewer than twenty mushers and 150 courageous dogs. They

would mush 24 hours a day for eight days, all day, all night.

The teams would face minus 75 degree weather and winds so high

they would actually blow the sleds over. Finally, Gunner Kassden,

behind 12 Huskies and the lead dog Balto, having covered the

final 54 miles of the relay, and suffering from frostbite arrived

on Front Street at dawn amid hurricane force winds and minus

50 degree temperatures (picture left, Gunner Kassen and Balto).

The serum was intact and Dr. Welch administered

what there was to the worst cases. Two days later a second

dogsled relay delivered enough serum for everyone else. Still,

the record shows seven died, although Dr. Welch believed there

may have been a hundred more deaths in the villages surrounding

the town , and that hundreds, even thousands had been saved

by the efforts of the sled teams.

All mushers received full

recognition and medals were presented them personally by the

Governor of the Alaskan Territories. But the news stories centered

on Kaasen and his dog, Balto. Singled out as representative

of all the heroes of the effort, Kaasen and Balto were renowned

world wide with Balto, a huge black Husky, becoming more famous

than Rin Tin Tin. |

|

|

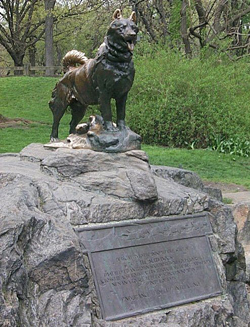

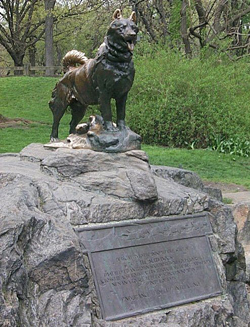

| (Left) As early

as December of that year a bronze statues of Balto was

unveiled in Central Park, New York City. Balto was in attendance

at the dedication and also appeared to a crowd of 20,000

in Madison Square Garden. (Right) A statue of Balto also

now stands in downtown Nome. |

|

Perhaps

the fame Balto and his harness mates earned with there stamina

and courage would have served them well had it not been for

the greed of one promoter. Just two years after their epic

journey, Balto and six of the participating Huskys were discovered

unhealthy and poorly treated at a sideshow in downtown Los

Angeles by the visiting Cleaveland business man George Kimble.

A deal for the dogs was struck. $2000 would be required to

free the dogs. This was a huge sum in 1927 and Mr. Kimble

went to the Cleveland newspapers with the story. The city

raised the money in two weeks and on March 19, 1927, Balto

and his six companions were given hero's welcomes in a parade

through downtown Cleveland. The city supported the dogs in

the dignity their courage had earned them for the rest of

their lives (picture left, Balto - 1925). Perhaps

the fame Balto and his harness mates earned with there stamina

and courage would have served them well had it not been for

the greed of one promoter. Just two years after their epic

journey, Balto and six of the participating Huskys were discovered

unhealthy and poorly treated at a sideshow in downtown Los

Angeles by the visiting Cleaveland business man George Kimble.

A deal for the dogs was struck. $2000 would be required to

free the dogs. This was a huge sum in 1927 and Mr. Kimble

went to the Cleveland newspapers with the story. The city

raised the money in two weeks and on March 19, 1927, Balto

and his six companions were given hero's welcomes in a parade

through downtown Cleveland. The city supported the dogs in

the dignity their courage had earned them for the rest of

their lives (picture left, Balto - 1925).

Don’t

miss the gripping near minute by minute account of the events

of December 1925 through Feburary 1926 at Wikipedia - 1925 serum run to Nome Don’t

miss the gripping near minute by minute account of the events

of December 1925 through Feburary 1926 at Wikipedia - 1925 serum run to Nome

Read why it was decided not to attempt the rescue with aircraft

and find out how the story became world news that January.

Discover the rest of this inspiring story and view a wonderful

collection of period photographs at Earl Aversano’s

great website “Balto’s True Story”here:

http://www.baltostruestory.com/serumrunsynopsis.htm

Discover why it is that when the Iditarod teams get together

today, they revier the musher Seppala and his lead dog Toro as

the true heros of the event.

Visit the history depicted at Nome’s

http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~aknome/balto.html |

| Read the story in Gay and Laney Salisbury's book, “The

Cruelest Miles: The Heroic Story of Dogs and Men in a Race

Against an Epidemic.” and watch for Walden Media’s

film adaptaion of the book scheduled to begin shooting this

summer. |

|

| |

Visit www.barnstormers.com -

post an ad to be viewed by over 700,000 visitors per month.

Over 14 years bringing more online buyers and sellers together than any

other aviation marketplace. |

Copyright © 2010

All rights reserved.

|

| UNSUBSCRIBE INSTRUCTIONS: If you no longer wish to receive this eFLYER, unsubscribe here or mail a written request to the attention of: eFLYER Editor BARNSTORMERS, INC. 312 West Fourth Street, Carson City, NV 89703. NOTE: If you registered for one or more hangar accounts on barnstormers.com, you must opt out of all of them so the eFLYER mailings will be fully discontinued. |

|

Finding

out why drew me in to one of those special stories, common

knowledge to some, but totally unknown to the rest of us.

Finding

out why drew me in to one of those special stories, common

knowledge to some, but totally unknown to the rest of us.  Which

was fine, most of the time. In normal circumstances the residents

coped well. They kept in contact with one another; checked on

the neighbors; stayed aware of who came and went (picture

right, Front Street in Nome, Alaska).

Which

was fine, most of the time. In normal circumstances the residents

coped well. They kept in contact with one another; checked on

the neighbors; stayed aware of who came and went (picture

right, Front Street in Nome, Alaska).  So why do I bring this

up here on an aircraft site? Because if you’ve followed

many of my stories in past Eflyers you know I like to write

about heroes and it took a lot of heroism to save the people

living around Nome that winter.

So why do I bring this

up here on an aircraft site? Because if you’ve followed

many of my stories in past Eflyers you know I like to write

about heroes and it took a lot of heroism to save the people

living around Nome that winter.

Perhaps

the fame Balto and his harness mates earned with there stamina

and courage would have served them well had it not been for

the greed of one promoter. Just two years after their epic

journey, Balto and six of the participating Huskys were discovered

unhealthy and poorly treated at a sideshow in downtown Los

Angeles by the visiting Cleaveland business man George Kimble.

A deal for the dogs was struck. $2000 would be required to

free the dogs. This was a huge sum in 1927 and Mr. Kimble

went to the Cleveland newspapers with the story. The city

raised the money in two weeks and on March 19, 1927, Balto

and his six companions were given hero's welcomes in a parade

through downtown Cleveland. The city supported the dogs in

the dignity their courage had earned them for the rest of

their lives (picture left, Balto - 1925).

Perhaps

the fame Balto and his harness mates earned with there stamina

and courage would have served them well had it not been for

the greed of one promoter. Just two years after their epic

journey, Balto and six of the participating Huskys were discovered

unhealthy and poorly treated at a sideshow in downtown Los

Angeles by the visiting Cleaveland business man George Kimble.

A deal for the dogs was struck. $2000 would be required to

free the dogs. This was a huge sum in 1927 and Mr. Kimble

went to the Cleveland newspapers with the story. The city

raised the money in two weeks and on March 19, 1927, Balto

and his six companions were given hero's welcomes in a parade

through downtown Cleveland. The city supported the dogs in

the dignity their courage had earned them for the rest of

their lives (picture left, Balto - 1925).  Don’t

miss the gripping near minute by minute account of the events

of December 1925 through Feburary 1926 at

Don’t

miss the gripping near minute by minute account of the events

of December 1925 through Feburary 1926 at